Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape is credited with ushering in the whole 90s indie movie scene. It took home the top 3 prizes at Cannes Film Festival – best film, best actor and the international critics’ prize. Then it went to Sundance and secured wide distribution from Miramax, turning a solid profit with a small budget, and the film catapulted Soderbergh to status of promising director with a distinct authorial voice.

I’ve watched many of Soderbergh’s films, but for some reason, Sex, Lies, and Videotape eluded me for a long time. Maybe it’s the title – which promised some kind of seedy titillation that would be an awkward watch while still living with my parents – but more realistically my film education hadn’t progressed till I was more advanced in age. The film is the same age as me, so it feels fitting to watch it now when I myself am married, and in some way can better comprehend the themes of the film. It’s a beautiful film: outstanding performances, naturalistic dialogue – I love how the actors trip over their words a little like how we would in real life – and a stellar screenplay that helps us sink so easily into the lives of these characters.

The film starts with Ann (Andie MacDowell) talking about garbage, and her preoccupations with the world being overwhelmed with too much trash. This isn’t the first time Ann gets caught up talking about world problems as a way to distract from her own personal issues. The reason why she’s at therapy is because her marriage lacks intimacy. She isn’t particularly interested in sex with her husband John (Peter Gallagher), but has noticed that he’s stopped initiating sex. Ann’s flustered when asked about masturbation, and doesn’t indulge in any of her sexual feelings, with or without her husband. While Ann’s pouring her heart out in therapy, her husband John is having sex with her sister Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo) – a double dose of betrayal which Ann might have intuitively sensed even if she didn’t explicitly know.

In breezes John’s college friend Graham (James Spader), who’s come to stay with them for a bit while he finds his own place. Ann’s initial skepticism regarding Graham vanishes when she meets him. She’s intrigued by him, and it seems like the feeling’s mutual. One of the first things Graham asks her is whether she’s ever been on television. It’s definitely complimentary, and when we learn of his videotape fetish later on, it pretty much confirms his attraction to her. At dinner, he’s focused on Ann and her needs, offering to help clean up, and refusing any sense of camaraderie with John because he’s a liar. When Graham compliments Ann, John uses the compliment as a means to criticise her. It’s not to say that married couples can’t playfully tease each other, but John’s remarks feel mean-spirited and he seems intent on judging Ann rather than appreciating her. We come to realise that the lack of sex in Ann and John’s marriage is symptomatic of a larger issue in their relationship; if the bedroom is dead, is there still life in the relationship?

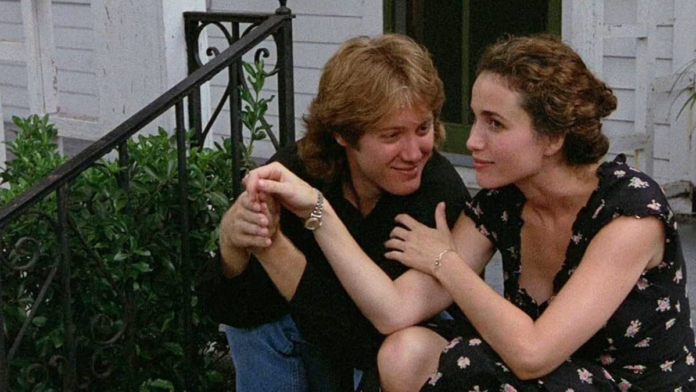

It’s the inverse for Ann and Graham, who seem to be gradually building intimacy as they spend time together. Ann accompanies him while he’s house hunting – the apartment for 2 remark by the landlord is certainly symbolic – and when they eat out after, they share a plate of food. All of this reflects their ease and comfort with each other, so much so that Graham confesses his impotency to her.

Ann tells her therapist that she doesn’t really enjoy sex, nor does she initiate it. This is different with Graham, as she actually goes to watch him while he’s sleeping. Watching someone sleep is such an intimate act, something we only do with our lovers, so it is here that we see Ann’s burgeoning sense of desire, but it’s not for her husband. John doesn’t care to know her, and because of that their marriage lacks intimacy, which is why she can’t be honest about sex with him. When she showed disinterest, instead of exploring the why and trying to connect with his wife to improve on things, John decides to do the easier thing and sleep with her sister.

It’s no coincidence that both Ann and Cynthia leave John after experiencing some form of intimacy with Graham. Cynthia realises that sex does not equate true intimacy, while Ann never desired her husband the way she desires Graham. Soderbergh’s film emphasizes that technology can impede human connection and intimacy. Graham was using the videotapes to build a faux sense of intimacy so he could get off – a mere voyeur taking pleasure from the objectification of his subjects. His previous breakup messed him up so much he created a whole system that would keep him safe from emotional intimacy. Ann is the only one to turn the camera on him, the other women were content to remain subjects of Graham’s admiration and focus. Her desire to know him and help him is what allows him to break free from his crutch on the videotapes. Ann and Graham move on to build something beautiful together, while John remains stuck in his web of lies.

And now in the 21st century, there are even more technological distractions that serve to impede and create distance in relationships: couples looking at their phones at a restaurant and barely talking, the instant gratification accorded by online material, preoccupations with devices and gaming. Maybe put down the phones and talk to each other, even if it’s about the weather.